By: LAURIE ROGERS

Assistant Director of Public Relations and Publications

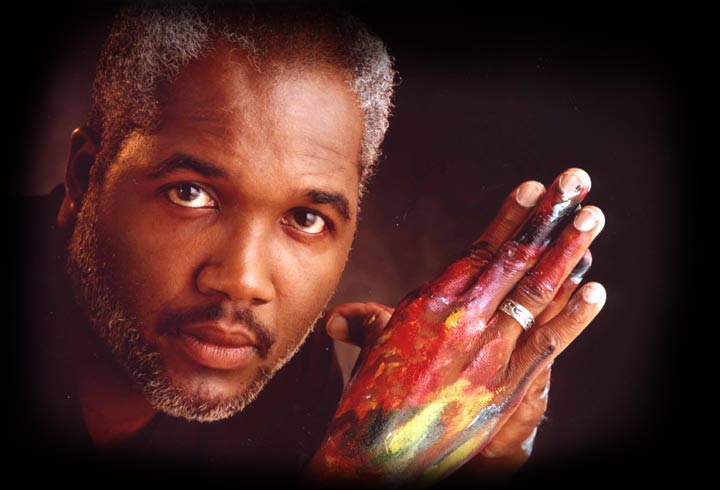

Posey was born Aug. 28, 1964, in Fort Bragg, N.C. His father,

Marvin Posey Sr., a captain in the Army, traveled throughout the

nation with his family-- son, Marvin; daughter, Angela; and wife,

Annie-- before being stationed at Fort Campbell, Ky., where the

family finally settled.

Even as a child, Marvin Posey Jr. was fascinated by color, mixing

different packets of Kool-Aid together to create new colors and

flavors.

"Color plays an important role in our lives," he says. "Most

people take that for granted." But for him, colors "kind of evolve."

"Sometimes it's by accident, and sometimes I just go with the

flow," he says. "I can see color on the blank canvas. I'll conceive

of the colors, and then I'll just blend the paint until I get what I

see."

But Posey, 32, didn't start out doing oil-based works.

Intimidated by paint, he initially worked with color markers, pastel

and pencil, impressing his family and teachers with his natural

talent and winning many contests.

As a student at Clarksville High School, he had an exhibit at the

Knoxville Museum of Art. Teachers and fellow students nominated and

awarded him with the "Artist of the Year" award. In his senior year,

he was asked to create numerous illustrations in the "Teacher's

Southern Association Handbook." When he graduated, he was awarded

with a double scholarship: one for football and one for the arts

program at Austin Peay.

But even with all his success, Posey was reluctant to apply

himself to his art. He says it wasn't because he felt pushed to be

something he wasn't. "My family has always shared a closeness, and

my mother and father encouraged me to follow my dream and be the

best that I could be at whatever I do." Instead, Posey's reluctance

stemmed from a fear that he didn't have what it takes to make it.

After his high school graduation, he enlisted in the Marine Corps

reserves and spent a summer in boot camp before enrolling in Austin

Peay's graphic design program.

At Austin Peay, he tried to follow in his father's footsteps,

playing football for the University. But his heart wasn't in it. "I

found myself on the (football) field, and I thought, `I'm not really

into this.' I never really applied myself."

He also wasn't into the graphic design degree. Assignments for

him seemed like just another day in class. "I was too scared to pick

up a paint brush," he recalls. "I was afraid of failure. I was

afraid I wasn't a real artist."

He was, however, a dancer. An avid fan of Michael Jackson, Posey

would practice Jackson's steps over and over. Word of his dancing

got around, and Posey was offered a chance to strut his stuff during

the Govs' half-time show. He practiced for months and even lost

weight so he'd look more like Jackson. The crowd of about 3,000

seemed to enjoy his performance, he recalls, adding that he's still

a huge fan of Jackson's music.

Even though the graphic design degree didn't appeal to him, Posey

says the art classes he took at Austin Peay did benefit his art, by

influencing how he approached a piece; how he viewed the focal point

and the foreground; how he built a composition.

At the Feb. 2 exhibit at Austin Peay, Bruce Childs, associate

professor of art, was reflecting on where Posey was as a student and

how far he'd come. "That means a lot to me, coming from a

professor," Posey says.

Posey also fondly remembers Max Hochstetler, professor of art,

who taught him watercolor. "(Max Hochstetler) gives me good

feedback. The times he's critiqued my work, he's been proficient and

sincere. I'm not afraid of getting my feelings hurt because I have a

lot of confidence, and there's always room for improvement."

But Posey is speaking of today; 12 years ago, that confidence in

himself and his art had yet to surface.

In 1985, still searching for a future to hang his heart on, Posey

left Austin Peay and joined the Army, again trying to do as his

father had done. He spent four years in the Army as a cook, while he

daydreamed about being an artist.

Faced with the fairly basic Army food, Posey's artistic skills

would not be stifled. Using everything from vegetables to fruit to

coconut, he would garnish the meals to brighten them up. Stealing a

chapter from his childhood, he mixed different flavors of Jell-O and

garnished that, too.

"Sometimes I would get carried away, and sometimes the food would

be late," he admits with a sheepish grin. "But when the food did get

out there, the soldiers appreciated it. The only complaint I would

ever get is that there might be too much garnish."

Posey got back into his art while stationed in Fort Devon, Mass.,

when he was challenged by a friend to do a drawing of a unicorn. He

used prisma-color pencils and was impressed by the result.

"I could see it was still in me," he says. "It was my destiny for

it to blossom." But even though he began again to enter art

competitions, he still refused to see it as a way of life, instead

as just a way of escape from a structured Army life.

It was during a tour of duty in Korea that Posey's eyes finally

opened to his artistic potential. Shopping for art supplies one day,

he met Maria Kohl, a professional artist, who recognized his talent

and began to encourage him to do more and to work with paint.

Shortly thereafter, with her encouragement, he produced his first

professional art exhibit in Korea, from which several of his 15

prisma-color works were sold.

Discharged in 1989, Posey returned home to Clarksville and opened

his first Austin Peay art exhibit. More than 400 artists, students

and community members attended. He realized at last the appeal of

his work, and he developed a whole new focus on his style. He

visited galleries, read articles and found inspiration in the

techniques of the great masters like Picasso, Van Gogh and Matisse.

In a last attempt to put his art on a back burner, he worked for

a time as a Clarksville firefighter. He did some modeling and acting

and appeared in a music video. But each time he tried to stray away

from his art, he says, something would pull him back: a commission,

a sale, a successful exhibit. Finally, he accepted what his heart

already knew: Painting was to be his future.

Now, when he's painting, he feels "complete and in my own world,

being at peace with everything."

Posey's style still is evolving, and he considers himself a

student: still learning, still trying to improve his style and

technique.

When he becomes intrigued by a theme, he wants to explore it in

all its facets. The type of music he listens to while he paints

inspires him, and the faster the music, the faster the brush stroke.

When he wants to paint a love theme, he'll listen to Toni Braxton.

Someone who once caught him listening to Michael Jackson while he

painted noticed that he was dancing along with the music.

"You don't realize how much you get into it," he says, laughing.

He knows a piece is finished, he says, by gauging its crispness

and clarity and by seeing that there's nothing else to add. "I

achieve the finished look by having the appearance of complete

balance, dark and light contrast and, finally, color harmony."

Posey's successes are varied and evolving at a rapid pace; it

isn't easy to keep up with his latest designs, projects and shows.

As of the writing of this article, he had designed an original tie

for President Bill Clinton, which was to be presented to him as a

gift through Posey's contacts in Washington. The design is an

abstract design of Clinton playing the saxophone. Posey's work was

to be featured, and a print auctioned, at a fund-raiser for

Professional Athletes Association in Chicago, in conjunction with a

jazz concert by Najee. Posey was to design a tie or vest as a gift

for the artist.

At the Women's Museum in Washington, he was the only contributing

male artist who donated a painting for the fund-raiser. He has shown

his work at the New Orleans Jazz Festival, the Chicago Jazz Festival

and at his debut in Washington. Other projects: displays in a

Washington, D.C., restaurant; a cover for a CD album for The Blues

Doctor and the Yellowjackets; a display of a piece on Fox Network's

"Living Single"; an on-the-air interview at a festival in

Chattanooga. Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, Sheila E., Louise

Mandrell, Charles Dutton and Howard Hewitt own some of his works.

A look at a more recent theme of his-- portraits of artists such

as Jackson, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Sadé, Jimi Hendrix and

Humphrey Bogart-- reflects Posey's interest in color rather than

race. He says this is deliberate.

"I want my work to not just appeal to one race, but to everyone,"

he says, while admitting that other people sometimes make it an

issue anyway. Some call his work "not black enough." One woman told

him he had to start putting some "white" people in his paintings.

"There are certain stereotypes," Posey says. "If you deal with

black galleries, they want black images. But my area is universal.

It's from my life experience.

"The world is in many different colors. I've seen people try to

separate on both sides. But everybody is equal; we're all human. I

try to stress that in my work, the harmony. Some people will be

offended by that, but that's the way I was brought up.

"I've been waiting for this to happen-- to be respected as a

human. To not be judged by my skin color but by my contribution."

Told once that he tends to underprice his art, he prefers to let

the galleries handle questions of market value.

"But there comes a time when you have to make a break," he notes.

"You could be a Pinto or you could be a Lamborghini. I want to be a

Rolls Royce."

Meanwhile, Posey is working hard to get his name and his work out

in the public eye in as many venues as he can. He's even donated

many pieces to various entertainment establishments and

organizations. He donated "Heart and Soul" to Austin Peay's

Candlelight Ball Feb. 22, and several pieces went to the Bourbon

Street Blues Club in Nashville.

"Donating gets your foot in the door," Posey says. "People see

your work. There was a time I couldn't let a piece go. Now I see

what it means to someone to have one of my paintings. It's like a

piece of me on canvas.

"This is something I'll enjoy to the day I die. I feel like this

is my destiny. I won't live forever, but my work will. I'm leaving a

legacy, and so I'll always be here."

For more information about Marvin Posey's artwork, call

1-888-415-1053 or write Rod S. Wentz, Posey Executive Marketing

Director, P.O. Box 10764, Fargo, N.D., 58106.

----------------------------------

One my family members |